“Adagio d’Amore” (Adagio from Oboe Concerto in D Minor by Alessandro Marcello), performed by Hauser and London Symphony Orchestra:

Courtesy of Iryna Palok:

Some years ago, courtesy of my daughter Samantha, an alumna of this college, I attended a seminar on early plant hunters held at Christ Church, Oxford. The magnificent architecture of Christ Church holds you spellbound, with its ancient quadrangles, the sweeping staircase that leads to the stately dining room where you share your cordon-bleu meals with the greats of this country, looking down at the diners from the portraits lining all the walls. Among the poets, writers, and philosophers, there are also thirteen Prime Ministers, including Peel and Gladstone.

The founder, Cardinal Wolsey started work on Cardinal College in 1525 and by 1528, one of his assistants wrote: “Every man thinks the like was never seen for largeness, beauty, sumptuous, curious and substantial building.” After failing to secure Henry VIII’s divorce, Cardinal Wolsey fell from grace and his work stopped. Henry VIII re-founded the college as Christ Church that unusually included the cathedral. I particularly like to visit there the ancient sarcophagus of the knight John de Nawers, who rests for eternity with his faithful companion, his dog at his feet.

The Great Tom, the gate-tower entry to the Christ Church, has a bell that chimes while students hurry along to their lectures. It is at Christ Church that Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) wrote about the dream world of Alice in Through the Looking-Glass. I write so much about Christ Church because any seminar held there becomes a much grander, more inspiring event that intensifies the whole experience. And one last thing – the locations for Hogwarts in the Harry Potter films were inspired by Christ Church hall and the Divinity School.

“Hedwig’s Theme” (from Harry Potter) by John Williams, performed by Vienna Philharmonic (courtesy of Sony Classical):

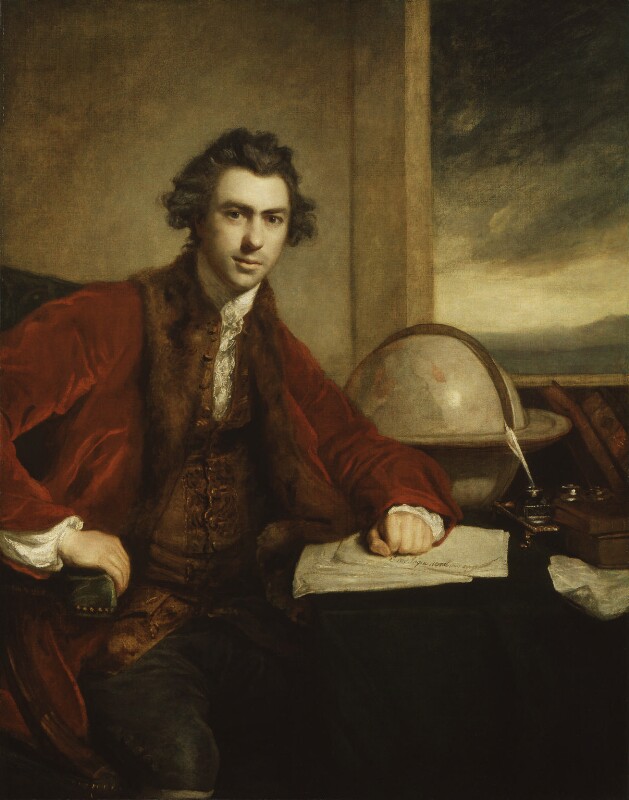

Joseph Hooker

The plant hunters seminar included the work of Joseph Hooker born in 1817. At that time there were no scientists as the word had not even been invented. By the time he died, the concept of, and the word, ‘scientist’ was well established. This was the time of enlightenment and discovery. After graduating with a degree in medicine, he enlisted as an assistant surgeon and botanist on HMS Erebus for a four-year expedition to the Antarctic. From that voyage, he came back with 1,500 preserved plant species. In 1847 he embarked on a second expedition, lasting three years, this time to India and the Himalayas of Nepal and Tibet.

He brought back a unique collection of 7000 plant species, including 25 new species of rhododendrons, then almost unknown in British gardens. After publishing his findings in Himalayan Journals, dedicated to Darwin, he was appointed the assistant director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, becoming a director in 1865. During his many expeditions, he identified more than 12,000 new plant species in his lifetime. He died at age 94 and is buried in St Anne’s Church on Kew Green, just outside the gates of Kew Gardens.

Courtesy of Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew:

Joseph Hooker was by his own description, an enthusiastic amateur, who like Darwin his closest friend, could unrestrainedly pursue what he wanted when he wanted and where he wanted. There was just one problem, and that was a lack of income. He struggled financially until he became the assistant director at Kew. Over the years he developed life-long friendships with other enthusiasts living in far-flung parts of the globe, who too shared his love of plants and supplied him with many plant species. In his published journals are included his precise sketches/drawings of plants he collected and the places he visited. Joseph Hooker was called a botanical trailblazer; it was fully justified, as his passion for plants and his dedication to finding them was unsurpassed. During his expedition to the Himalayas, he found the rarest of orchids, a blue-flowering one that grows in woods of dwarf oak. The orchid mania at that time was at its highest. At one London auction, the orchids were sold complete with human skulls in which they were grown, as promised to the original owners, a tribe in Colombia.

“Den Reisende (The Traveller)” by Debbie Wiseman, performed by The National Symphony Orchestra of London:

In Whitby – the replica of Captain Cook’s ship The Endeavour and his statue

During my stay at Whitby a few years back, I visited Captain Cook’s museum as Whitby was his hometown. His home is preserved exactly as it was when he lived there, with the dining room table beautifully set and a dish of roasted chicken (not real!) served. The top floor is full of his maps, and many finds he brought back from his travels. Among them is a life-size figure of a penguin. During the Antarctic expedition, there was a pet penguin on board the ship. He was tame, ran around the sailors and shared their meals from their plates. The harbour in the town is dominated by Captain Cook’s ship, the replica of HMS Endeavour and the statue of the great explorer looking wistfully out to sea.

Courtesy of British Library:

When Captain James Cook in 1768 embarked on the Endeavour to start a four-year expedition to the Pacific islands, he had with him a wealthy naturalist philosopher Joseph Banks, a botanist. He brought with him on the voyage a retinue of nine people, including two talented draughtsmen. Only two out of the nine returned to Britain; Sydney Parkinson who painted 1332 drawings of Banks’ plants, was among those who never made it home. Well connected and wealthy, Banks was instrumental in creating Kew, and supplying it with many plant species from far away places. Joseph Banks was the product of Harrow School, Eton, and Christ Church, Oxford. When he left after graduation, he had extensive knowledge of natural history, in particular, botany.

Joseph Banks, by Sir Joshua Reynolds

His travels, enthusiastic plant collecting, and studies of the natural history of Newfoundland and Labrador, and his expedition with Captain Cook to the Pacific Ocean brought him recognition. He became the President of The Royal Society in 1777 where he remained until his death in 1820. He was knighted in 1781 in recognition of his achievements. He introduced to Britain and Europe acacia, mimosa, eucalyptus, and Banksie, a genus named after him.

The 18th century was a time of an explosion of interest in natural history and social changes. In the period between the death of Carl Linneaus and the rise of Darwin, an unknown artist of humble beginnings emerged who was to be established as the best of the botanical artists (on a par with Redoute), and the most knowledgeable natural historian, called James Sowerby. His books on flora and fauna and other studies made him greatly sought after by plant collectors and scientists.

And now to the last great plant hunt, and the worldwide famous, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London. The exquisitely presented book – ‘The Last Great Plant Hunt, the story of Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank’ tells a fascinating story. The quest of the scientific team there is to preserve the seeds of all plant species. David Attenborough described this as ‘perhaps the most significant conservation initiative ever.’ In ten years more than 3.5 billion seeds from nearly 25,000 species have been collected, in partnership with 120 institutions in 54 countries. As Patron of the Foundation and Friends of The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, His Royal Highness Prince Charles wrote in the Foreword: ‘Seeds are one of Nature’s marvels; they are cunning and highly evolved to meet all manner of environmental challenge’, and later on: ‘Increasingly, seeds play a vital role, not only in ensuring the survival of the plants that expand enormous energies to produce them, but in the survival of our planet and humankind itself.’

“Myrtle” by Debbie Wiseman; Myrtle was first described by Swedish botanist Linnaeus in 1753 (courtesy of ViolinAround):

Dr. Eric Chivian, the Nobel Peace Prize winner from Harvard Medical School who specializes in biodiversity, concluded that: ‘Plants are absolutely fundamental to life; they provide us with the air we breathe, help to supply our water, the houses we live in, the food we eat and the medicines that heal us.’ It would not be possible to present here the incredible work carried out by Kew scientists in all corners of the world. By chance, a friend, Violetta Rybak once visited the Botanic Garden in Chicago, where Kew’s work is also carried out, and sent me some pictures of this beautiful place. Among the pictures of flowers, there is a sculpture of Carl Linneaus, sitting among some of the thousands of plants that he catalogued.

Courtesy of chicagobotanicgarden:

The last word has to go to Paul Smith, Kew’s Head of Seed Conservation, about the work that is carried out: ‘A quest to save biodiversity before it is too late.’

Courtesy of Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew:

“Chi Mai” by Ennio Morricone (courtesy of Nikos D):

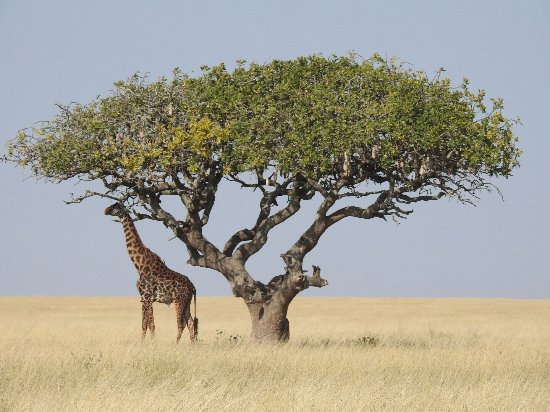

Amazing sculpture… I thought it was a tree that grew to become like that.

LikeLike

Thank you, Chen Song Ping, for your kind comments, which are much appreciated!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are wc, joanna!

LikeLike

Thank you, Chen Song Ping!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

So we could say you’re hooked on Joseph Hooker.

LikeLike

Thank you, Steve, for your amusing comment, which is much appreciated!

Joanna

LikeLike

Hello Gaby. Here you manage to convey a deep respect and devotion for botany, reminding us of the essential role of plants in our history, culture and future. It is a tribute to human curiosity and the intimate connection between nature and humanity.

A reading that inspires to look with new eyes at plants and to value more those silent explorers who, thanks to their passion, enriched our world. 🌿💚

LikeLike

Thank you, Lincol, for your beautiful comments, which are much appreciated!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

🤗🤗🫂🤗

LikeLike

Thank you!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person