Courtesy of Harrusito:

“People often say that I’m curious about too many things at once…

But can you really forbid a man from harbouring a desire

to know and embrace everything that surrounds him?”

“Our imagination is struck only by what is great;

but the lover of natural philosophy

should reflect equally on little things.”

Alexander von Humboldt

Goldberg Variations: Aria by J. S. Bach, played by Igor Levit (courtesy of Findebaran):

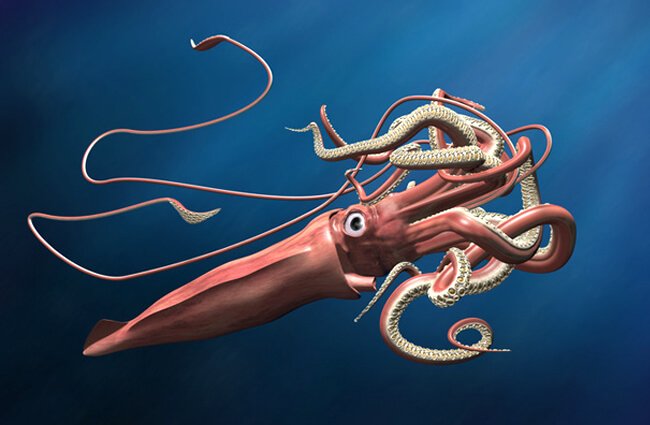

Alexander von Humboldt (1769 – 1859), is called ‘the great lost scientist’ for good reason. There are towns, rivers, mountain ranges, the Humboldt Current that runs along the coast of Chile and Peru, dozens of monuments, parks, and mountains in Latin America including Sierra Humboldt in Mexico and Pico Humboldt in Venezuela, a town in Argentina, a river in Brazil, a geyser in Ecuador, a bay in Colombia, then a Kap Humboldt and Humboldt Glacier in Greenland, a mountain range in northern China, South Africa, New Zealand and Antarctica, also rivers and waterfalls in Tasmania and New Zealand, as well as parks in Germany and Rue Alexandre de Humboldt in Paris, also in North America alone four counties, thirteen towns, mountains, bays, lakes and a river, the Humboldt Redwoods State Park in California and Humboldt Parks in Chicago and Buffalo, also almost 300 plants including the Californian Humboldt lily, and and more than 100 animals, including the South American penguin and the six-foot ferocious Humboldt squid, also several minerals like Humboldtit and Humboldtin, as well as an area on the moon called ‘Mare Humboldtianum’ – all named after him. To this day many German-speaking schools across Latin America hold a biannual athletic competition called Juegos Humboldt – Humboldt Games.

“The Ecstasy of Gold” by Ennio Morricone, played by Hauser:

Introducing Alexander von Humboldt:

Below is the Paracas coastline in Peru:

Below is Humboldt Redwoods State Park in California:

Experience the magic of Redwood National Park (courtesy of National Geographic):

One man’s mission to revive the last Redwood Forests:

Below are Humboldt Falls in Milford Sound, New Zealand:

Waterfalls in Milford Sound (courtesy of bellamoonnature):

As early as 1800, Humboldt predicted human-induced climate change and his contemporaries called him ‘the greatest man since Deluge’; he really influenced the way we see nature today. He provided proof that nothing exists in isolation; he found connections everywhere and demolished the view of the tunnel vision where a plant, a tree or a forest are all examined as individual cases, unrelated to each other.

“Everything is interaction”, part 7 of “On the Humboldt Trail”:

Humboldt was the first to notice and explain the forest’s ability to enrich the atmosphere with moisture and its temperature lowering effect, as well as its importance for retaining water and protecting against soil erosion.

Coastal redwoods of California (courtesy of Craig Philpott):

The two pictures below are of Humboldt National Park in Cuba:

Humboldt’s intellect and his prolific writing influenced many thinkers, artists, and scientists, including Charles Darwin, who wrote: ‘nothing ever stimulated my zeal so much as reading Humboldt’s ‘Personal Narrative’, and that ‘he would not have boarded the Beagle, nor conceived of the Origin of Species, without Humboldt.’ Thomas Jefferson called Humboldt ‘one of the greatest ornaments of the age’. The great poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge put Humboldt’s concept of nature in their poems. Henry David Thoreau, the most loved and respected of America’s nature writers found an answer to his dilemma of how to be a poet and naturalist in one. Simon Bolivar, who liberated South America from Spanish colonial rule, called Humboldt the ‘discoverer of the New World’. Germany’s greatest poet, Johann Wolfgang Goethe, wrote that spending a few days in Humboldt’s company was like ‘having lived several years.’

Below is a portrait of Simon Bolivar, liberator of South America:

Andrea Wulf, the renowned Humboldt biographer, wrote: ‘ We are shaped by the past. Nicolaus Copernicus showed us our place in the universe, Isaac Newton explained the laws of nature, Thomas Jefferson gave us the concept of liberty and democracy, and Charles Darwin proved that all species descend from common ancestors. These ideas define our relationship to the world. Humboldt gave us our concept of nature itself.’

Here, I have to express my profound admiration and respect for Andrea Wulf and her extraordinary, unique approach to writing a biography of a giant of science, Alexander von Humboldt. Where most biographers would read all the papers, notes, letters and books relevant and stored in the libraries of the big cities, Andrea had done all that, but then she has religiously followed in the dangerous footsteps of the explorer. She climbed the living volcanos, sailed across the oceans, hiked in Yosemite, travelled in the rainforest in Venezuela, listening to the strange bellowing cry of howler monkeys.

The sounds of wild howler monkeys (courtesy of CostaRicaColor):

On Chimborazo, the mountain that had been so important to Humboldt’s vision of nature, she crawled to the top of a few centimetres wide ridge, with steep precipices on both sides, and after getting to the top, she suffered the same lack of oxygen, that Humboldt did, and found the air so thin that her legs felt leaden and seemingly detached from her body. Her quest was to restore Humboldt to his ‘rightful place in the pantheon of nature and science’. I don’t know of any other biographer who would willingly risk her/his life in the process of doing so, and I can only bow in admiration. She is also an acclaimed writer of several books and her sophisticated and elegant writing adds greatly to the pleasure of following the adventures of Alexander von Humboldt.

Here Andrea Wulf discusses her book:

Andrea Wulf’s heroic efforts to bring back to us the lost hero of sciences made me wish to spread the word about this remarkable man too. My blog has been read in 168 countries worldwide, from Canada to New Zealand, from South Africa to Argentina, across Russia, China, Hong Kong, the United States, India to Malaysia, Philipines, Japan, Indonesia and Nepal, Afghanistan, Guyana, Singapore, Oman, Palestinian Territories, Armenia and several European countries, including Great Britain, also the United Arab Emirates and Nigeria, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Albania, Algeria, Morocco, Thailand, Bangladesh, Taiwan, Turkey, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Brazil, South Korea, Venezuela, Paraguay, Tunisia, Iraq, Colombia, Oman, Georgia, Maldives, Myanmar (Burma), and many more (statistics provided by WordPress), and perhaps it would be useful, was my thought, if I were to write about this great man, based on Andrea’s fascinating biography ‘The Invention of Nature’. I feel that I can write about the geographical extent of my blog because I am not selling anything and don’t have adverts benefiting me in any way. I should add here that I don’t think that so many people read my blog because my writing is so interesting, but because I write ABOUT interesting people, events or plants and animals. Otherwise, I would be labouring under a delusion, so well described by Oscar Wilde, who quipped: ‘I am so clever that sometimes I don’t understand a single word of what I am saying’.

Here is a map of the world, provided by WordPress, showing in purple all the countries where some people have read my blog:

The facts about the beginning of Alexander von Humboldt’s life are as interesting as they are complex. He was born into a wealthy aristocratic Prussian family in 1769, at Tegel, a country estate ten miles from Berlin. Alexander was nine when his much-adored father died suddenly. From then on, Alexander and his older brother, Wilhelm were left in the care of the excellent tutors, as their mother never showed the boys any affection. Fortunately, she provided them with the best education by teachers who would instil in them a love of truth, liberty and knowledge. From a very young age, Alexander would take every opportunity to explore the countryside around the estate, when not confined in the classroom, collecting plants and rocks. He found nature calming and soothing, after hours spent poring over Latin, maths and languages. The time he was born into was called the Enlightenment. Those were times of global changes, revolutions, expansions, industrial developments. The publishing, opening of the new universities and libraries raised the level of literacy. The great thinkers and inventors were providing ways of harnessing nature, among them Voltaire, Benjamin Franklin, and Isaac Newton. The Humboldt brothers, now grown up, joined Berlin’s intellectual circles. They both studied at various universities in preparation for becoming civil servants as their mother insisted, but Alexander dreamed of distant travels, of filling the gaps on world maps and collecting exotic plants. A chance meeting with a crew member of one of Captain Cook’s ships resulted in a few months tour abroad, and after wanderlust won, Alexander would never become a civil servant, much to his mother’s displeasure.

Below is Humboldt in later life in his library:

Adagio For Violin and Orchestra in E Major, K.261, by Mozart, played by Daniel Hope and the Zurich Chamber Orchestra:

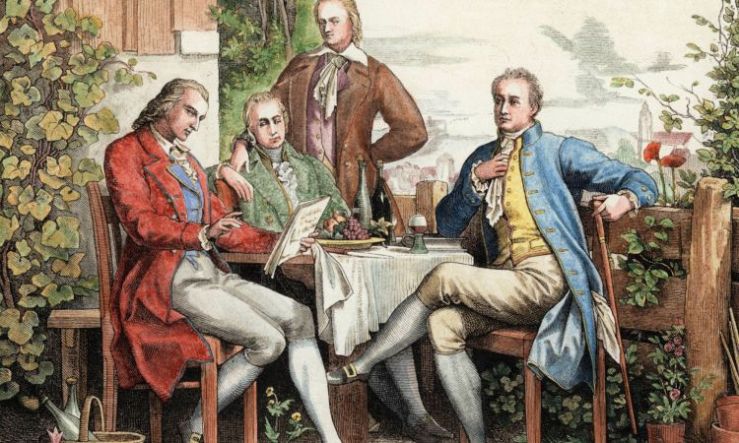

In the late eighteenth century, scientific dogmas about nature began to change. Humboldt’s passionate goal at that time was to undo what he called the ‘Gordian knot of the process of life.’ It was during a visit to his brother, who was now married and had settled 150 miles from Berlin in a small place, Jena, fifteen miles away from Weimar, the state capital, and the home of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, that Humboldt met Germany’s greatest poet. A young man, Alexander, ignited in Goethe a spark that was missing in the then middle-aged Goethe’s life. They discussed their ideas about nature and walked and dined together, and conducted experiments. One of their contemporaries said that in Weimar ‘the brightest minds came together like the sunrays in a magnifying glass.’

The picture below shows a discussion between Schiller, Goethe and the two Humboldt brothers in Weimar:

Knowing Goethe only for his literary achievements, I could now understand his answer, when asked ‘why are we here?’ – ‘I am here to wonder.’ I wrote about this in my post ‘I am here to wonder’ as urbanisation and technology (read computer games) have disconnected many people from nature. Reading Andrea’s biography enlightened me about Goethe’s work as a scientist who was fascinated by the formation of the earth and botany. He also worked on comparative anatomy and optics. In the young Alexander, he found a stimulating partner who would make him ‘dizzy with ideas’. His writing of Faust coincided with Humboldt’s visits and it reflected his relentless striving for knowledge. Knowing Goethe affected Humboldt profoundly and showed him a new way of looking at nature. I was delighted to learn that Goethe was also a passionate, professional gardener. At that time Humboldt’s mother died and finally, at twenty-seven, he was ready and financially able to begin his travels and the search of his destiny.

“Passaggio” by Ludovico Einaudi, performed by Daniel Hope and Jacques Ammon:

Having bought all the latest instruments he would need to measure, map and see things in the distance, Humboldt embarked on the frigate ‘Pizarro’ that was waiting for him in Spain. As they sailed towards the tropics, his excitement increasingly grew. He tested his instruments, measured the height of the sun, and examined the fish, jellyfish, seaweed and birds. When one night the sea seemed to be on fire with phosphorescence, he wrote in his diary that it was like ‘edible liquid full of organic particles.’

This bioluminescence is similar to what von Humboldt may have seen (courtesy of Filippo Rivetti):

They stopped briefly in Tenerife, and he rushed ashore to climb the first mountain outside Europe, the volcano Pico del Teide. After climbing 12,000 feet to its peak, his face was frozen but his feet were burning from the hot volcanic ground. The journey continued and when he saw the Southern Cross, he wrote that he had achieved the dreams of his ‘earliest youth’. Forty-one days after leaving Spain, he saw the first sight of the New World, Venezuela. South America at that time was in Spanish hands and governed with absolute rule. Humboldt knew that despite having a passport issued by the king of Spain, he could have serious problems unless he managed to inspire an interest in those who were in charge of the colonies. For a moment he enjoyed the tropical scenery, everything new and spectacular. It was to be the beginning of a new life, and the five years spent there would change him from ‘ a curious and talented young man into the most extraordinary scientist of his age.’

Over the next few months, Humboldt, his assistant and a manservant moved along towards the tropical jungle to find if two major rivers, Orinoco and Amazon were connected, as he suspected. It was here his observations lead him to write: ‘When forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by the European planters, with impudent precipitation, the springs are entirely dried up, or become less abundant. The beds of the rivers, remaining dry during the part of the year, are converted into torrents, whenever great rains fall on the heights. The sward and moss disappearing with the brush-wood from the sides of the mountains, the waters falling in rain are no longer impeded in their course: and instead of slowly augmenting the level of the rivers by progressive filtration, they furrow during heavy showers the side of the hills, bear down the loosened soil, and form those sudden inundations, that devastate the country.’

“Gabriel’s Oboe” from “The Mission” by Ennio Morricone:

As I have described Andrea’s efforts to follow in Humboldt’s footsteps as he explored the world, I will only add the interesting fact – one hundred years after Humboldt’s death, in 1869, Alexander Humboldt’s centennial was celebrated across the world. There were parties, celebrations, and monuments unveiling from one end of the globe to another. Andrea’s quest to restore the memory of this greatest of scientists will no doubt be successful.

By way of a concluding tribute, an excerpt from “Forests” by Louie Schwartzberg (courtesy of Colin Farish):

Thank you, Ashley for your kind comment! Happy reading!

Joanna

LikeLike

The data of how many read your blog, and the extent across the globe, is testament to the fact that you are so passionate in sharing your research and knowledge of people, places, events, nature, and the striving of others to share our wonderful world and universe. Thank you, once again, for your tremendous efforts Joanna.

LikeLike

Thank you, Peter, for your wonderful and kind comments!

All greatly appreciated! I will do my best!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are absolutely right, Joanna, when say that “People often say that I’m curious about too many things at once…

But can you really forbid a man from harbouring a desire to know and embrace everything that surrounds him or her? But then that is so very natural thing to happen! You have presented nature in a very mesmerising way through your photos and lovely videos! Great share! I also endorse the views of my learned friend Arun Singha on this beautiful post 🌷🙏

LikeLike

Thank you, Dhirendra, for your wonderful comments!

Your words are greatly appreciated!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure,Joanna 🙏🙏

LikeLike

Thank you again, you are very kind!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Joanna. Their cleverness is making sure I loose my left over hairs 🙃

LikeLike

You are welcome!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

Namaskar! Jai Bharat 🇮🇳

LikeLike

Tathastu! Jai Bharat!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙏🙏🙏

LikeLike

I read Andrea Wulf’s biography of Humboldt several years ago. I agree with you that schoolchildren should be taught about him and his discoveries—but then, at least in the United States, schoolchildren are taught less and less about everything significant. Humboldt would be duly appalled.

LikeLike

Joanna, another great post. You are such a fantastic researcher, you turn information into a good story. Wonderful!

LikeLike

Thank your, Monica, for your wonderful comments! Your words make me happy and a greatly appreciated!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Steve, for your insightful comments. That is why I write about important people, places and events.

Thank you, Steve, again, your thoughts are greatly appreciated.

Joanna

LikeLike

Joanna,

Thank you for enlightening me on the scope of the influence of Alexander von Humboldt. I have encountered his name several times and never realized that the geographic features were named for a man. How uncurious we can be about some things while at the same time being curious about so much!

I have explored on foot the Humboldt Redwoods (in Humboldt County, CA) and blogged about them (twice) and for including David Milarch’s life goal of planting replacements for all of the Redwood trees we have killed by cutting them down! I have taken an early morning bird walk after eating a takeout breakfast in the Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge on Humboldt Bay, and driven past the Humboldt Mt. Range (and also the Humboldt River and lake) in Nevada. I knew about the Humboldt Ocean current and the Humboldt Penguin. I did NOT know that he inspired George Perkins Marsh whose name is first on the National Park where I volunteer because he lived in the mansion there and wrote Man and Nature, one of the first books on ecology and climate change. Could it have been Humboldt who planted the thought seed that each of earths inhabitants influence the others who are proximate or distant?

Humboldt, the name and the man will now have a proper place in my cerebrum from this day forward. And be certain, I will find and read Andrea Wulf’s biography of this pioneer in science. Thank you for writing about him and his work. Stewart

LikeLiked by 1 person

Than you, Stewart, so much for your eloquent and interesting comments! Nothing please me more than a response like yours to my post, especially your promise to read the book!

I will read and re-read your comments a few more times, Stewart,

as your words made my day! A Big Thank you!

Joanna

LikeLike

To be honest, I never heard of Humboldt. I always learn something new from your posts. Thank you!!

LikeLike

Humboldt’s passion for knowledge and his relentless pursuit of truth are truly inspiring, Joanna. It’s absolutely fascinating knowing the story of Humboldt’s early life, his encounters with Johann Wolfgang , and his transformative journey to South America. It’s so inspiring.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Ritish, for finding time to read and wonderfully comment on another post! I am so glad that you thought Humboldt’s story interesting.

It was my aim to bring him back into public domain.

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely ❤️

Loved reading about him.

LikeLike

Thank you again, Ritish!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

Feed the beautiful soils, the beautiful soils feed the plants, and the plants really do take care of us! Lovely post Joanna!

LikeLike

Thank you, Dorothy, for your kind comments! Your thoughts are greatly appreciated!

Joanna

LikeLike

Well researched and written Joanna. It is curiosity that leads all explorers. I have heard his name often on geographical features around the world, including when we visited Milford Sound twice. Why is it we hear so much about Cook, Darwin and Vancouver, but so little about Humboldt? Thanks for sharing. Allan

LikeLike

Thank you, Allan, for your wonderfully thoughtful comments! That is the question that made me write this tribute to Humboldt. He was an extraordinary man and left an astonishing legacy of knowledge!

Thank you again, Allan, for your time and thoughts which are deeply appreciated!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person