“In every walk with nature one

receives far more than he seeks.”

John Muir

“The Color of the Sky” by Chad Lawson:

“All of our discontents for what we want appear to me

to spring from want of thankfulness for what we have.”

“Robinson Crusoe”, Daniel Defoe

“Infinite Gratitude” by Lisbeth Scott:

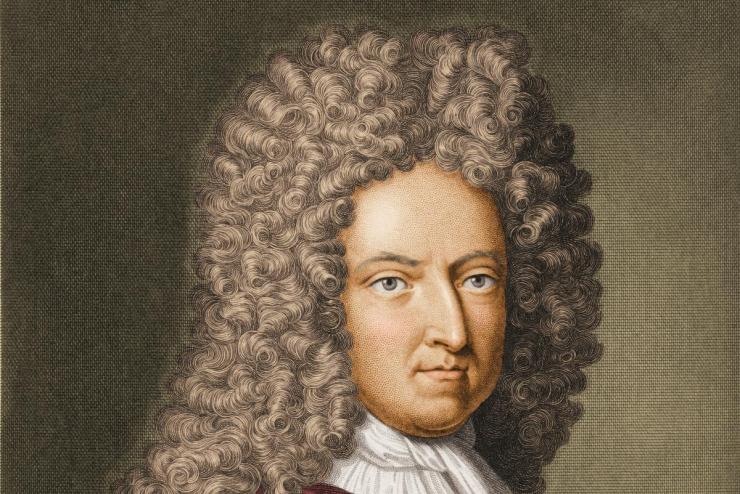

DANIEL DEFOE

1660 – 1731

Courtesy of Course Hero:

Daniel Defoe was born in London, the son of a butcher. His father wanted him to become a minister (priest), but he preferred to go into a trade as a hosiery merchant, among other money-making schemes. He took part in Monmouth’s rebellion against James II in 1685, and while hiding in a churchyard he noticed the name, Robinson Crusoe carved on a gravestone and later gave it to his famous hero.

Defoe first achieved notoriety for a satirical pamphlet, The Shortest Way With the Dissenters (1702), which landed him in prison for seven months, but this failed to deter him from political writing. He had trouble finding a publisher for Robinson Crusoe (1719), but it was later to become his most famous work and is now claimed by many critics to be the first true novel.

The first edition of the novel

Moll Flanders (1722) and Roxana (1724) followed, and altogether he wrote an astonishing 560 works in his lifetime, including travel guides, journals, and many more inflammatory pamphlets. He died in 1731 at his lodgings in Ropemaker’s Alley in London’s Moorfields.

Defoe’s monument grave in London

“Equinox: 1” by Oliver Davis, performed by Kerenza Peacock and Budapest Scoring Orchestra, conducted by Peter Illenyi:

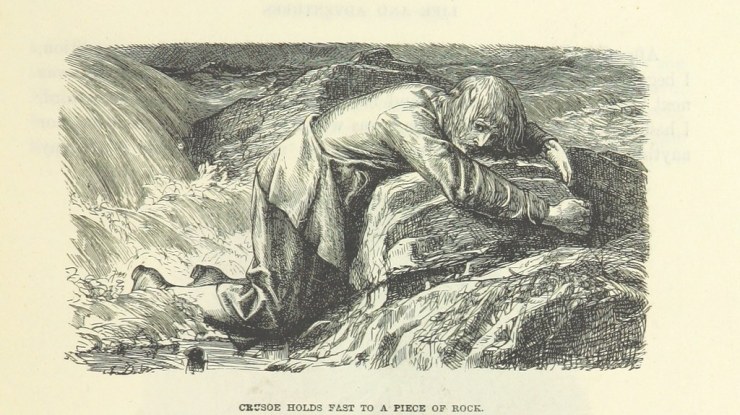

ROBINSON CRUSOE

Courtesy of Oxford Academic:

In one of the world’s most famous stories, Robinson Crusoe is shipwrecked on an island somewhere in the Pacific and wrestles with loneliness and despair as he struggles to stay alive. With the ingenious use of some supplies and utensils salvaged from the ship, he manages to build a house and then a boat, and forage enough food to live on.

Should you ever need it, how to survive on a desert island (courtesy of How to Survive):

One day, years later, he finds a footprint in the sand and realises he is not as alone as he had thought.

The story is simple and compelling: against the advice of his father, a young man eschews the boring certainties of a comfortable life and runs off to sea in search of adventure. Despite misfortune on his first voyage, he persists in pursuing the promise of travel, until at last, he finds himself on a desert island, the sole survivor of a shipwreck.

Crusoe overcomes his despair and applies himself to creating a home in his unfamiliar surroundings. For the next two decades, in solitude, he re-creates in his island wilderness as much as he can of the civilised world.

From the book’s opening sentence, Crusoe addresses, Crusoe addresses the reader in a voice – direct and declarative in a manner of casual speech, that was something new in literature. But it is only when Crusoe begins building his lonely habitat, narrating in matter-of-fact detail his projects and activities, that Defoe’s genius truly takes hold.

As Nobel Laureate J.M. Coetzee has observed, “For page after page – for the first time in the history of fiction – we see a minute ordered description of how things are done.” What Coetzee terms Defoe’s “pure writerly attentiveness” highlights what he describes with unexpected presence:

“By being a great artist and forgoing this and daring that in order to give effect to his prime quality, a sense of reality – Defoe comes, in the end, to make common actions dignified and common objects beautiful. To dig, to bake, to plant, to build – how serious these simple occupations are; hatchets, scissors, logs, axes – how beautiful these simple objects become. Unimpeded by comment, the story marches on with magnificent downright simplicity.”

And we march with it, until, like Crusoe, we are brought up short by a footprint on the beach:

“It happened one day about noon,” we read, “going towards my boat, I was exceedingly surprised with the print of a man’s naked foot on the shore, which was very plain to be seen in the sand.”

With this startling discovery, Defoe’s story opens out to welcome first “my man Friday,” whom Crusoe saves from cannibals, and then the victims of another shipwreck. By the time he is rescued himself after twenty-eight years, Robinson Crusoe can embark for England from the midst of a small community that has taken root in the long-lonely precinct of his ordeal.

But not before, alone on his island, he has cast a narrative spell that has enthralled readers for over three centuries. The book has had many film adaptations over the years.

An extract from Robinson Crusoe:

“September 30, 1659. I, poor miserable Robinson Crusoe, being shipwrecked during a dreadful storm in the offing, came on shore on this dismal, unfortunate island, which I called ‘The Island of Despair; all the rest of the ship’s company being drowned, and myself almost dead.

All the rest of the day I spent in afflicting myself at the dismal circumstances I was brought to – vis. I had neither food, house, clothes, weapon, nor place to fly to; and in despair of any relief, saw nothing but death before me – either that I should be devoured by wild beast, murdered by savages, or starved to death for want of food. At the approach of night I slept in a tree, for fear of wild creatures; but slept soundly, though rained all night.

October 1. In the morning I saw, to my great surprise, the ship had floated with the high tide, and was driven on shore again much near the island; which, as it was some comfort, on one hand – for, seeing her set upright, and not broken to pieces, I hoped, if the wind abated, I might get on board, get some food and necessities out of her for my relief – so, on the other hand, it renewed my grief at the loss of my comrades, who, I imagined, if we had all stayed on board, might have saved the ship, or, at least, that they would not have been all drowned as they were; and that, had the men been saved, we might perhaps have built us a boat out of the ruins of the ship to have carried us to some other parts of the world.

I spent a great part of this day in perplexing myself on these things; but at length, seeing the ship almost dry, I went upon the sand as near as I could, and then swam on board. This day also continued raining, though with no wind at all.”

Statue of Alexander Selkirk in Fife, Scotland

Courtesy of Welcome to Fife:

Defoe based his novel on the true story of Alexander Selkirk (1676-1721), a Scottish sailor who was put ashore on the uninhabited South Pacific island of Juan Fernandez in 1704, and was marooned for four years there until 1709. His extraordinary first-person narrative is a convincing psychological study of an individual in extreme circumstances, and Defoe’s great talent is to make you feel as if you are there, experiencing it alongside Crusoe.

“These Memories” by Hollow Coves:

With his parrot and parasol, the castaway Crusoe is an emblem of survival, self-sufficiency, resourcefulness, and ingenuity that shapes civilisation from the raw materials of nature.

“By The Sleepy Lagoon” by Eric Coates (courtesy of Barry Hodgson):

PS As a child, I was so under the spell of this book that Crusoe’s method of working became mine for life.

Thank you, Dwight, for your kind comment. Yes, indeed, what could one do?

Your thoughts are greatly appreciated!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are very welcome, Joanna!

LikeLike