“Difficulties are things that show a person what they are.”

Epictetus

Courtesy of siflippant:

The advancement of the sciences is not the only factor affecting discoveries, the economic and political necessities of the time are another. It is impossible, however, to ignore the rule of chance in the fate of a discovery. Whatever the role of luck, it must not be over-estimated, and we should acknowledge that a large part must be played by the attitude of the researcher and his observation skills. A stroke of luck there may be, but in scientific research, it is not purely accidental.

Before Photography (courtesy of George Eastman Museum):

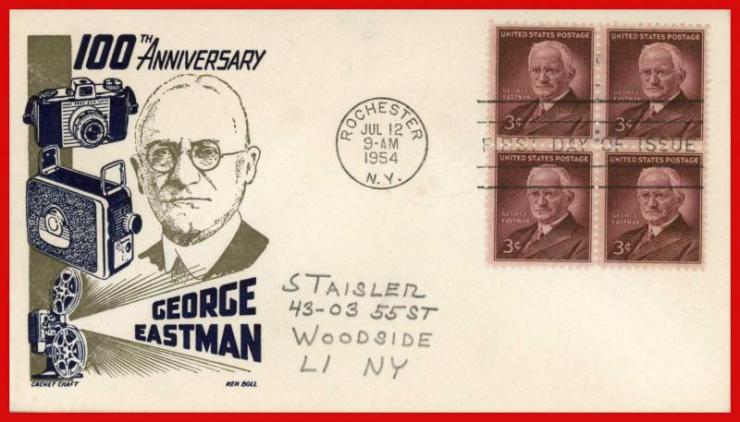

GEORGE EASTMAN

12 July 1854 – 14 March 1932

In its first fifty years, photography was the preserve of a relatively small number of professionals and enthusiastic amateurs. It was expensive, time-consuming, awkward, and very specialised. All that changed in 1888, when American inventor George Eastman began selling a cheaper camera, which was also easier to use.

George Eastman was born on a small farm in New York State, USA. When he was five years old, the family moved to the city of Rochester, also in New York. His father died when George was just eight years old, and the family fell on hard times. As a result, George had to leave school aged 13, to find a job. He was keen to learn, though, and was mainly self-taught.

Rochester, New York

Courtesy of Ryan Green:

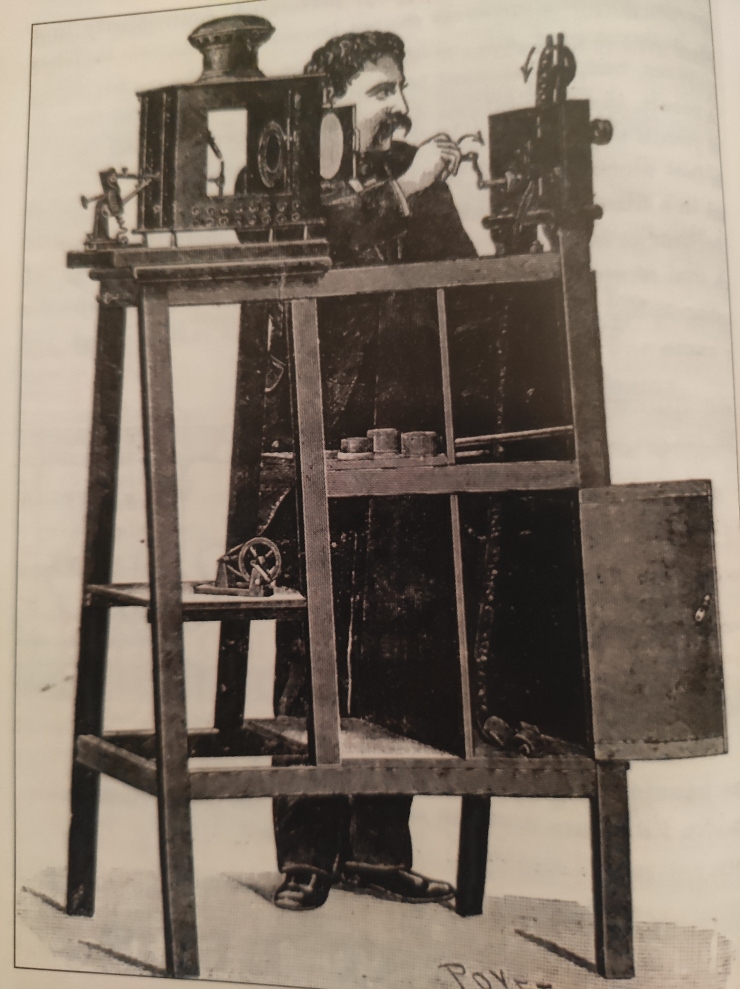

Eastman’s interest in photography was sparked at age 24 when, while working as a bank clerk, he planned a trip abroad. A colleague suggested he take a record of his trip, so Eastman bought a camera. The camera was a large, unwieldy box, which had to be mounted on a heavy tripod, and instead of film, there were individual glass plates that had to be coated with light-sensitive emulsion in situ and held in large plate holders. For outdoor shots, the plates had to be prepared in a portable tent that doubled as a dark room.

In 1878, Eastman read about ‘dry plates’, invented in 1871 by the English photographer Richard Leach Maddox. The emulsion was sealed onto the plates with gelatine. These plates could be stored, then used whenever desired, making obsolete much of the equipment Eastman had bought. While he was still working at the bank, Eastman devoted all his spare time to finding the perfect way to mass-produce dry plates.

Above is a dry-plate camera

In 1880, Eastman set up the Eastman Dry Plate Company. He began making and selling dry plates in 1881 and soon realised that glass could be replaced by a lighter, flexible material. In 1884, he had the idea of making the flexible plate into a roll. A roll holder could be mounted in place of the plate holder inside the camera. His first camera to feature a roll film, dubbed the ‘detective camera’, became available in 1885. The roll was made of paper, but this was far from ideal since the grain of the paper showed up on the prints. Meanwhile, other people were working on flexible dry plates, too. Several experimented with a material called nitrocellulose, also known as celluloid. Eastman began selling celluloid film in 1889. Eastman’s real stroke of genius was his realisation that to be successful, he would need to expand the market for photography, and that would mean, in Eastman’s own words, making photography ‘as convenient as a pencil’. To do that, he had to invent a new, smaller, affordable camera. In 1888, the first Kodak camera went on sale. It was an immediate success.

Below is Eastman’s first camera, the Kodak

The camera came loaded with a roll able to record 100 photographs. Once a camera’s owner had taken the pictures, he or she had only to send the camera to Eastman’s company and wait for the pictures and for the return of the camera, newly loaded with film. The key to Kodak’s success was changing the perception of photography to something that anyone could do it. Eastman had a simple phrase that did just that: ‘You just press the button, we do the rest’.

The first camera with mass-market appeal, the Kodak, retailed at $25 (5 shillings in the UK). This was only half what Eastman paid for the first camera he bought, but it was still prohibitively expensive for everyday photography. In 1900, the Eastman Kodak Company introduced the first of its most successful range of cameras: The Brownie. Eastman Kodak made and sold 99 different models of Brownies between 1900 and 1980.

The first Brownie was a cardboard box that contained a roll holder, a roll of film, and a lens. On the outside, there was a shutter button and a spool winder. The epitome of simplicity. It sold for just $1 (equivalent to about $20 in 2010) and brought in the era of the ‘snapshot’ – a photograph taken without preparation that can capture a moment in time which would otherwise be lost.

“One Moment In Time” performed by the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (courtesy of PlsSmile4Me):

After its introduction to still photography in 1925, 35mm roll film dominated the market in affordable photography until the introduction of consumer digital cameras in the 1990s. At the heart of a digital camera is a charge-coupled device (CCD). On the surface of this semiconductor chip are millions of light-sensitive units; each one stores and releases an amount of charge that depends upon the intensity of light that falls on it, and a computer translates those charges into digital information.

“Here Comes The Sun” by George Harrison, performed by Craig Ogden:

His famous quote: ‘Light makes photography. Embrace light. Admire it. Love it. But above all, know light. Know it for all you are worth, and you will know the key to photography.’

Above is Eastman’s house

Eastman changed the name of his company to Eastman Kodak and cornered the market in affordable photography. He never married, nor did he have any children. He was a great philanthropist, giving away large sums of money to universities, hospitals, and dental clinics. He was one of the first American Industrialists to embrace and implement the concept of employee profit-sharing. He made outright gifts from his own money to each of his workers. His generosity extended to many causes. He gave large sums of money to the struggling Mechanics Institute of Rochester, which became the Rochester Institute of Technology. His high regard for education led him to contribute to the University of Rochester and to the Hampton and Tuskegee institutes.

University of Rochester, New York

‘The progress of the world depends almost entirely upon education’, he wrote. In another quote, he expanded his belief: ‘The life of our communities in the future needs what our schools of music and other fine arts can give them. It is necessary for people to have an interest in life outside their occupations.’

Rochester Institute of Technology

Courtesy of Academy of Art University:

Dental clinics in Rochester and in Europe were also a focus of his concern. ‘It is a medical fact,’ he said, ‘that children can have a better chance in life with better looks, better health, and more vigour if the teeth, nose, throat, and mouth are taken proper care of at the crucial time of childhood.’

Eastman contributed $100 million of his wealth for philanthropic purposes during his lifetime.

His last two years were painful as he was suffering from a degenerative bone disease and at age 77 he took his own life in 1932 by shooting himself in the heart.

He left a note that read: ‘My work is done, why wait?’

“Lacrimosa” by John Brunning, performed by Xuefei Yang and Johannes Moser:

George Eastman Museum

Courtesy of Philip Dean:

Out of all the geniuses about whom I have written here, this Man has my greatest respect and affection.

“Photograph” by Ed Sheeran, performed by and courtesy of Daniel Jang:

AUGUSTE AND LOUIS LUMIÈRE

19 October 1862 – 10 April 1954 and 5 October 1864 – 6 June 1948

While no single person can be credited with inventing moving pictures, two French brothers, Auguste and Louis Lumière stand out for their foresight and their important contributions; using a film camera-projector that they designed, they put on some of the earliest public film screenings and helped to define cinema.

Courtesy of Ministry of Cinema:

Besancon, France

Courtesy of la belle aventure:

Auguste and Louis Lumière were born in Besancon, France, where their father Antoine had a photographic studio. In 1870, they moved to Lyon, and their father opened a small factory that made photographic plates. In 1882, Auguste and Louis helped to bring the factory back from the brink of financial collapse by mechanising the production of plates, and by selling a new type of plate that Louis had invented the previous year. The firm moved to a larger factory in Montplaisir, on the outskirts of Lyon, where it employed 300 people.

The Lumière Factory in Montplaisir

In 1894, the brothers’ father attended a demonstration of the Kinetoscope, a moving picture peep-show device developed at the laboratory of the American inventor Thomas Edison. The Kinetoscope was not a projector – only one person could watch a film at a time – but it was fast becoming popular entertainment. Antoine saw a commercial opportunity and, returning to Lyon, suggested his sons work on producing an apparatus that could record and play back moving images.

The Lumière Cinematographe

Louis, the more technically minded of the two brothers, designed the camera-projector, while Auguste designed the housing for the light source. Louis developed the film transport mechanism, inspired by a similar device in sewing machines, which allowed each frame of the film to stop momentarily behind the lens.

The Lumière brothers patented their camera-projector, the Cinematographe, in February 1895. Louis shot their first film, which was called ‘La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière a Lyon’ (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon), and the pair showed the film to the Societe d’Encouragement de l’Industrie Nationale, in Paris in March 1895, the first public screening of a film. The film was shot at 16 frames per second and, at that rate, it runs for just under 50 seconds. It features most of the nearly 300 workers – mostly women – walking or cycling out of the factory yard.

Courtesy of MediaFilmProfessor:

After several other screenings in France, their father arranged for the first performances to a paying audience. Ten films were shown 20 times a day. The opening night, at the Salon Indien – the empty basement of the Grand Cafe in Paris – was in December 1895. Auguste and Louis did not attend because they felt the technology still needed more work.

On July 7, 1896, the Lumière brothers showcased six films at the Watson Hotel in Bombay and this marked the birth of Indian cinema as we know it today. They arrived in India after having proved their cinematic excellence in Paris. By and by, skilled Indian painters — MF Husain was one of them — became adept at turning out giant Hindi film posters, few of which, sadly, have survived. Known today as the Esplanade Mansion, this building, which dates to 1869, is the oldest surviving cast-iron structure in India.

Below is Watson’s Hotel

Courtesy of Witty Box by TKP:

“Faded” by Alan Walker, featuring Iselin Solheim:

The Lumière Cinematographe was an all-in-one film camera, printer, and projector. For shooting, only the camera was needed: the wooden box. The magic-lantern lamphouse – the large black box – contained the light source for projection. The film holder can be seen protruding from the camera-projection box.

Below is an illustration of how the Lumière brothers were constantly improving their original design.

Courtesy of Joaquin Ignacio:

After a slow start, their show became a great success. In 1896, the Lumière brothers sent their agents abroad, demonstrating their Cinematographe and arousing great interest. They also ordered 200 or so of the camera-projectors to be constructed and opened agencies in several countries to sell them. The Lumière franchise was very successful, but they refused to sell their devices to anyone except through their own agent.

Below is the Lumière Cinematographe

By 1897, Thomas Edison had developed a system of sprocket holes that was incompatible with the Cinematographe and that was quickly becoming the standard in a rapidly developing industry. By 1905, Edison’s system would predominate and the Lumière brothers would leave the film business.

Auguste’s interests turned to chemistry and medicine. In 1910, he founded a laboratory in Lyon, where his 150 staff carried out research into cancer and other diseases. Auguste invented a dressing for burns, called tulle gras, which is still in use today, and pioneered the use of film in surgery, which helped a generation of medical students. Meanwhile, in the early 1900s Louis demonstrated a sequence shot on a new, wider-format film, and later experimented with panoramic and stereoscopic (3-D) films.

The Diamond Jubilee procession of Queen Victoria below

The Lumières’ film of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession in London, 1897 had circular sprocket holes, characteristic of the Lumières’ system. Other early filmmakers used 35mm film with rectangular Edison perforations, which became the industry standard. Later Cinematographes could run ‘standard’ 35mm film.

In 1904, the Lumière brothers perfected a colour photography system called Autochrome; they had been working on colour photography since the early 1890s. Autochrome was the most important colour photographic process until colour film became available in the 1930s.

The above colour photograph dates from c1910, taken with the Lumières’ Autochrome system. Shown are Andree Lumière (Auguste’s daughter), Suzanne Lumière (Louis’ daughter), Lazare Sellier (a friend of Antoine Lumière) and Josephine Lumière (Antoine’s wife).

When shooting, a glass slide coated with randomly scattered red-, green-, and blue-pigmented starch grains was held in front in front of the (black and white) film; the same slide was required for viewing.

Looking at the development of motion picture technology, from very early 1895, we can only admire the amount of inspiration required, also scientific research, superb manufacturing, skillful quality control, mechanical engineering and creative presentation, which made possible the illusion and magic of moving pictures. It is a huge story and only some aspects could be included here. My only regret is that the hundreds of brilliant and unseen people, those who worked in factories and labs, who made it all possible are not here either.

“Tara’s Theme” from “Gone With The Wind” (courtesy of zazapk9), one of the loveliest films ever made; two stills are shown below:

Joanna, your details which appear in this post have me wondering about many tangential issues. It is interesting that George Eastman, whose wealth came from Eastman Kodak, was so widely generous in his philanthropy. He must have been a forward thinking person. Placing an emphasis on education he donated locally to RIT and also distantly to two “HBCUs”. In the late 1800’s Rockefellers also donated to “Historically Black Colleges and Universities” which were the institutions primarily available for the education of black people after the US Civil War. Similarly, he gave bonuses to his employees and donated to medical institutions as well. The premise regarding good health and facial appearance was not lost on persons at the time. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, abolitionist and highly educated man, certainly understood the importance of visual image as he accurately portrayed the truth about black Americans prior to 1850. He became the most photographed black man, always immaculate in dress and grooming to promote his influence as a Negro.

My grandfather, a dentist, was a contemporary of George Eastman and this blog makes me wonder if donations to that profession led him to encourage my mother in photography. She was quite accomplished in the 1920’s when she had a dark room in their home, submitting images in traveling exhibits. Developing, printing and enlarging her images of Brattleboro’s older buildings, some now reside in the archives of the Vermont Historical Society Museum.

Also a curiosity, was the women’s suffrage movement in the latter half of the 19th century given an assist by photographic promotion? Almost certainly! Black and women’s rights were progressing on parallel paths simultaneously. And yes, before the days that women routinely drove motor cars, bicycles did provide a freedom and self-reliance. In her 70’s Susan B. Anthony understood “emancipation by bicycle” just as Lucy Ray (whose mom is an RIT professor), a Rochester, NY teen, graffiti artist does today. https://secondavenuelearning.com/susan-b-anthony-and-a-new-generation-of-voices-artist-feature-lucy-ray/

Who knows where curiosity will lead? Certainly you do, Joanna, or your multimedia written word would not be so engaging! Thanks for the ride.

LikeLike

Thank you for such informative comments. George Eastman is my hero. Writing about his tragic fate, I cry at the injustice as he was an exceptionally wonderful man.

Very interesting was your gifted mother’s connection with George Eastman. I am replying late because I publish my posts on Friday night.

Thank you again, greatly appreciated.

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person